-

Posts

14,195 -

Joined

-

Last visited

-

Days Won

680

Content Type

Profiles

Forums

Gallery

Downloads

Blogs

Events

Our Shop

Movies

Everything posted by red750

-

-

Maybe he didn't want his combover to blow around.

-

https://www.facebook.com/reel/1462478362176793

-

He wore a baseball cap to greet the 6 military personnel killed in his illegal war,

-

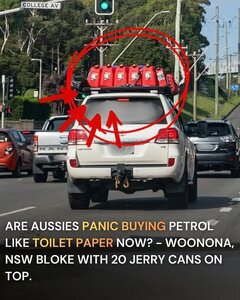

$130 billion wiped of ASX, petrol stations running dry. Prices skyrocketing.

-

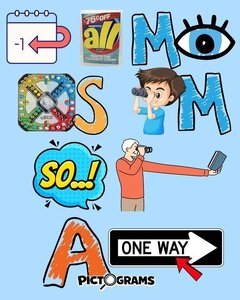

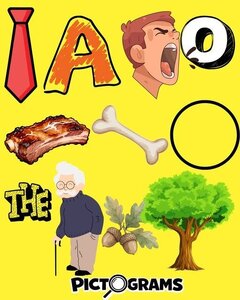

Two drug dealers are given a chance by a judge to avoid prison... The judge tells them, "You guys don't look like hardened criminals. I'll give you a deal: I'm releasing you for 24 hours. Your job is to go out and convince as many people as possible to quit using drugs. If you're successful, I'll drop the charges. Come back tomorrow and report your numbers." The next day, the first guy says, "Your Honor, I got 14 people to quit! I drew two circles: a big one and a tiny one. I told them the big one was their brain before drugs, and the tiny one was their brain after drugs." The judge is impressed. He turns to the second guy. "And you?" "I got 165 people to quit, sir!" The judge is stunned. "165?! Did you use the same 'brain' circles?" "Sort of," the guy says. "I pointed to the tiny circle and said, 'Listen up, boys... this is what your asshole looks like before you go to prison.'"

-

-

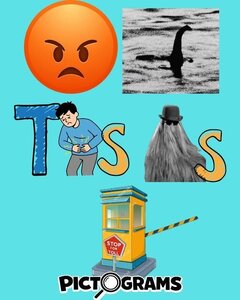

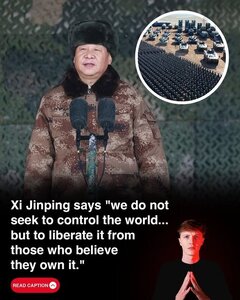

And that's the crux of it. Could all be BS.

-

Mary Trump explains why Donald is fighting the was against Iran. "Regarding his 'true' motivations, she claimed: "For Donald, there is one reason and one reason alone. He's in trouble, and he knows it. This isn't simply about changing the subject. That, of course, would be bad enough. "This is to keep himself and the world from knowing what an inept, depraved, compromised fraud he is. This is about his unfathomable desperation to avoid being humiliated." Mary Lea concluded by explaining that the President is a 'desperately weak man' who must distract people from this fact, adding: "That is a difficult tight rope for the weakest man I've ever known to be walking. "And yet, somehow, he has been allowed to walk it for his whole life. His whole miserable, useless, selfish life."

-

That change to the power system has caught Oscar out, resulting in a crash putting him out of the race before it starts. Crashed in the formation lap.

-

The ridiculous thing was petrol going up and down like a bride's nightie, from $1.59 to $2.29 per litre every few weeks, without a major war anywhere.

-

Most Poms wouldn't go that far by car on their holiday.

-

Well, Oscar will start from position 5, in row 3. Pole position went to George Russell from Mercedes. The big shock was Kimi Antonelli, who starts from P2. In practice earlier in the day, he virtually wrote off his car in a wild spin and crash. Not only did they rebuild the car in a couple of hours so he could take part in qualifying, he got the second best time to start from P2. Standby cars are not allowed. Lawson (Mercedes) is on P1, Antonelli (Mercedes)is P2, Hadjar (Red Bull) P3, Leclerk (Ferrari) P4, Piastri (McLaren) P5, Norris (McLaren) P6 . Max Verstappen spun out and did not set a time, so will start at the back of the grid.

-

Well known personalities who have passed away recently (Renamed)

red750 replied to onetrack's topic in General Discussion

Brisbane radio personality, comedian, singer and puppeteer, operator of Agro, Jamie Dunn, has passed away. He was aged 75. 4BC‘s Gary Hardgrave broke the news: “Apparently he woke up this morning not feeling too well, said to the love of his life Maree, ‘I’m going to go back to bed for a little while’ and unfortunately he passed away there. -

Trump and Hogsbreath have both said they don't give a damn about the law.